About Pablo Ramirez

Pablo Ramirez is the owner of El Mangal farm (named for the mango trees that proliferate in the area). The farm was founded by his father Alberto Ramirez, who bought the land in 1996. Pablo helped his father on the farm, then traveled abroad in search of better career opportunities. Pablo returned home in 2012 and has fully managed the farm since 2023. Currently, Pablo, his father, and his 5 dogs live on the farm. Apart from growing coffee, he also grows organic honey.

To get to his farm we have to fly to Oaxaca, travel for 4 hours by road to San Agustin Loxicha, then walk another hour along trails. He transports all his coffee via mule or on foot.

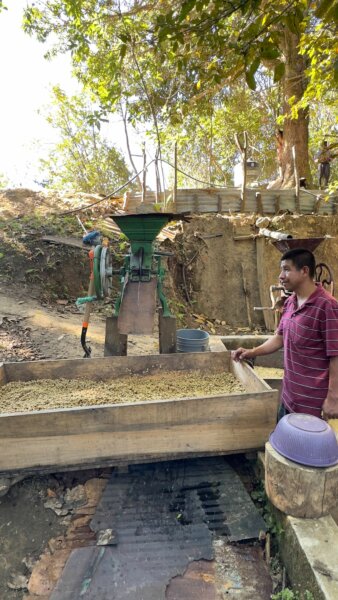

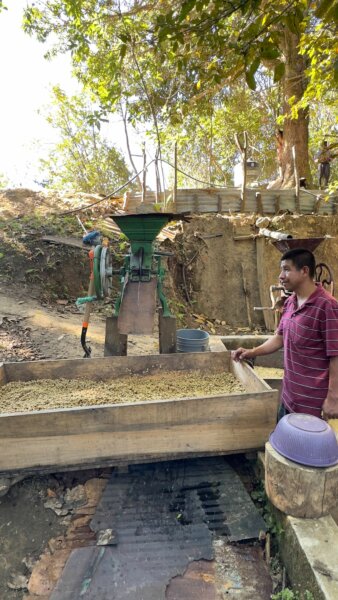

Pablo has his own washing station at his house, where he ferments the coffee in wood tanks for 24 hours, then dries it for 4 to 5 days on patios.

El Mangal usually keeps a distance of 2 meters between rows and 1.5 meters between seedlings. Between each row, Pablo places a plant that serves to separate the rows and keep the coffee trees apart.

Pablo uses native trees such as ice cream bean trees and avocado to shade their coffee trees. These trees provide not only shade, but also various benefits such as food, ornamentation, medicine, construction materials, and water retention. Pablo speaks English and Spanish.

The Oaxaca sourcing landscape is uniquely decentralized, presenting both challenges and opportunities for us as a sourcing company and for the communities and families we work with. As we continue to deepen our work in Mexico, we look at why Oaxaca is so different. Why aren’t associations or cooperatives as integral of a structure there as they are in so many other parts of Latin America or even Mexico?

The reason Oaxaca’s larger cooperative structures either dissolved or were abandoned by producers is primarily mismanagement on the part of the cooperatives there. What emerged from that dynamic was a push by producers to find trustworthy buyers directly, and eventually to find higher prices for their coffee within that model.

Our ever-expanding sourcing work in Oaxaca has been part of a large push by producers in the last five or six years to find buyers directly and get higher prices for their coffee. National quality competitions as well as regional competitions held by Red Fox have helped bring more attention to their coffee as a specialty product, as well as increased producer confidence that their coffee is valuable and should be treated as such. Mexico also has a very developed specialty cafe scene, which helped provide a local roasting market that was able to go out and buy coffee, which helped change the dynamic between producers and buyers. So all those factors led to producers looking for buyers like us: ones who would pay high prices for their coffee, pay exactly as we say we will, and provide consistency year after year.

Rebuilding that broken trust has been the hardest part of our work. There have been so many buyers over the years making promises of high prices, but the issues have been in the delivery. That’s why financing is such an important piece of the puzzle: more than anywhere else, Oaxaca’s producers are incredibly sensitive to the idea of trusting buyers to pay them later. As we’ve lived up to our word year over year, we’re starting to see that trust increase, which is incredibly rewarding and has caused producers to bring their family, friends, and neighbors into the fold. That’s why we see the level of voluntary community organization we see: the communities we work with have been waiting for an honest buyer who treats their product properly, and we’ve worked hard to be that buyer.